Chapter 2 Public Pressure: Why Do Agencies (sometimes) Get So Much Mail?

Abstract

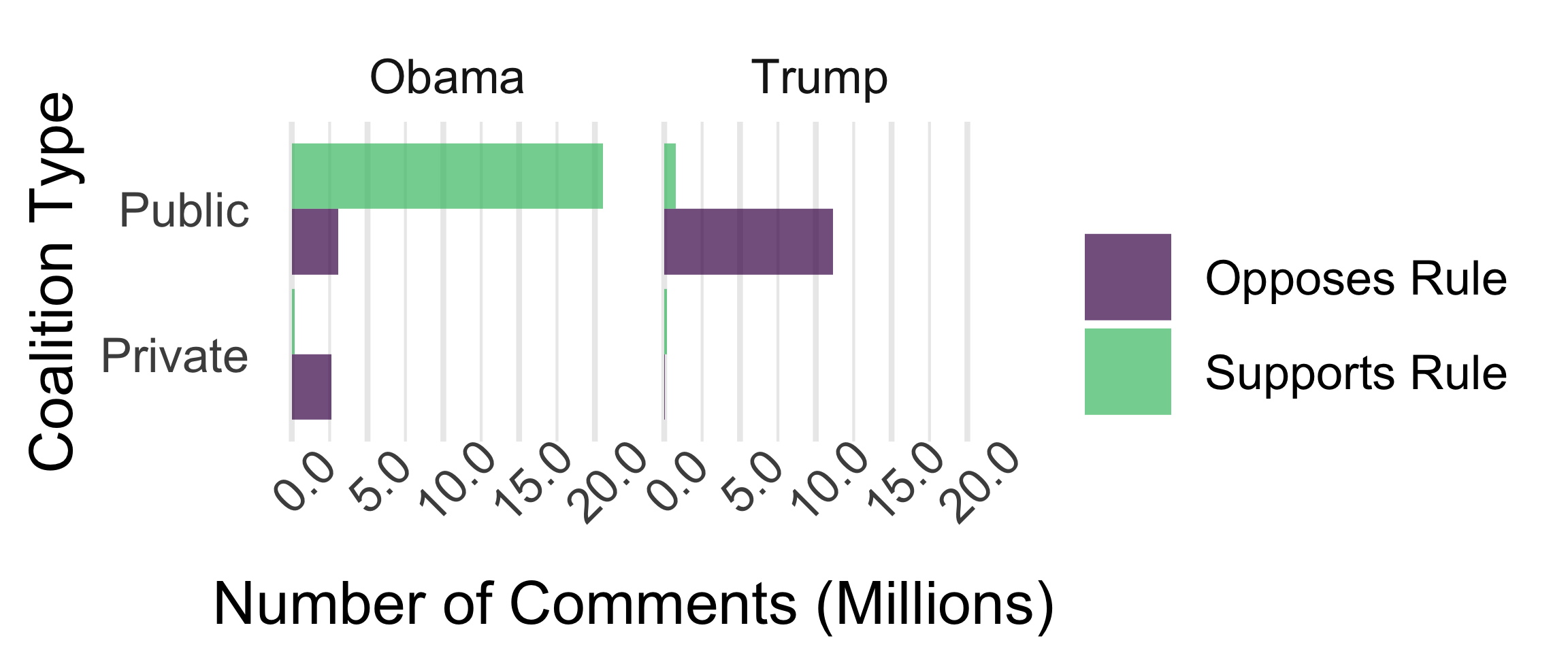

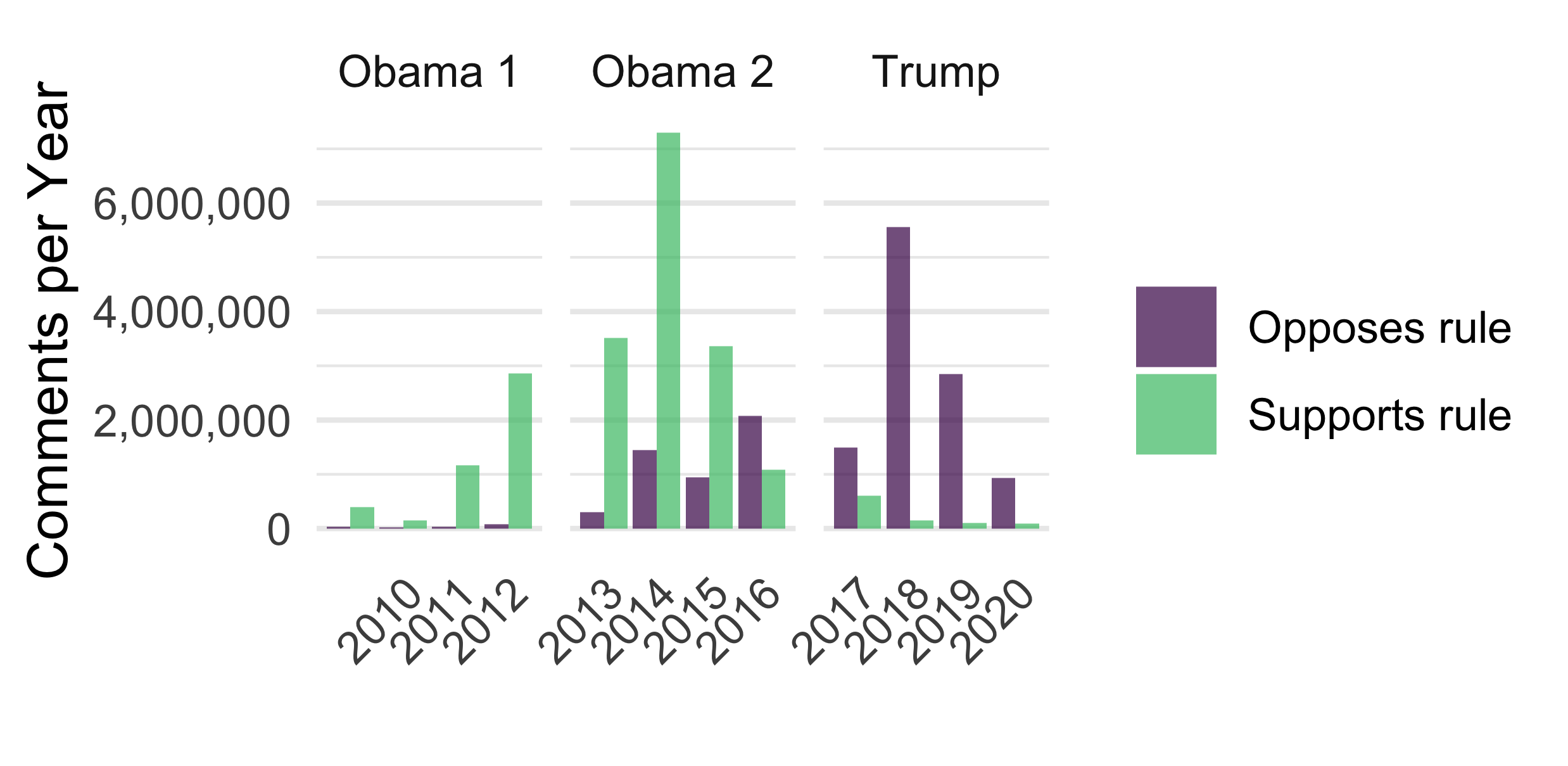

I examine who participates in public pressure campaigns and why. Scholars of bureaucratic policymaking have focused on the sophisticated lobbying efforts of powerful interest groups. Yet agencies occasionally receive thousands, even millions, of comments from ordinary people. How, if at all, should scholars incorporate mass participation into models of bureaucratic policymaking? Are public pressure campaigns, like other lobbying tactics, primarily used by well-resourced groups to create an impression of public support? Or are they better understood as conflict expansion tactics used by less-resourced groups? To answer these questions, I collect and analyze millions of public comments on draft agency rules. Using text analysis methods underlying plagiarism detection, I match individual public comments to pressure-group campaigns. Contrary to other forms of lobbying, I find that mass comment campaigns are almost always a conflict expansion tactic rather than well-resourced groups creating an impression of public support. Most public comments are mobilized by public interest organizations, not by narrow private interests or astroturf campaigns. However, the resources and capacities required to launch a campaign cause a few larger policy advocacy organizations to dominate. Over 80 percent of public comments were mobilized by just 100 organizations, most of which lobby in the same public interest coalitions. As a result, the public attention that pressure campaigns generate is concentrated on a small portion of policies on which these organizations focus. I also find no evidence of negativity bias in public comments. Instead, most commenters supported draft policies during the Obama administration but opposed those of the Trump administration, reflecting the partisan biases of mobilizing groups.

2.1 Introduction

Participatory processes like public comment periods on draft policies are said to provide democratic legitimacy (Croley 2003; Rosenbloom 2003), political oversight opportunities (Steven J. Balla 1998; Mathew D. McCubbins and Schwartz 1984), and valuable new information for policymakers (S. W. Yackee 2006; Nelson and Yackee 2012). The extent to which participatory processes make more democratic, accountable, or informed policy depends on who participates and why.

In civics classrooms and Norman Rockwell paintings, raising concerns to the government is an individual affair. Scholars, too, often focus on studying and improving the ability of individuals to participate in policymaking (Cuéllar 2005; Zavestoski, Shulman, and Schlosberg 2006; Shane 2009). But in practice, the capacities required to lobby effectively on matters of national policy are those of organized groups, not individual citizens (J. S. Hacker et al. 2021).

Bureaucratic policymaking, in particular, is the ideal context for powerful organized interests to dominate. Policies made by specialized agencies are likely to have concentrated benefits or costs that lead interest groups, especially businesses, to dominate (T. Lowi 1969; Theodore J. Lowi 1972; Wilson 1989). Agency policymakers are often experts who are embedded in the professional and epistemic networks of the industries they support and regulate (Gormley 1986; D. P. Carpenter, Esterling, and Lazer 1998; Dmitry Epstein, Heidt, and Farina 2014). Organizations with superior resources often flood policymakers with technical information valued both in the specific legal context of bureaucratic policymaking and technocratic rationality more broadly (Wagner 2010). Because agencies are generally framed as “implementers” rather than “makers” of policy, even the most value-laden policy documents are often framed as derivative of legislative statutes, even when these statutes are decades old. The assumption that Congress makes political decisions, not agencies, persists even as agencies write and rewrite policies that cite the same old statutes, advancing and reversing major policy programs under each subsequent president. All of these features—concentrated costs and benefits, the importance of expertise, and the anti-politics of the technocratic frame—privilege legal and technical experts and thus the organizations with the resources to deploy them.

And yet, activists frequently target agency policymaking with letter-writing campaigns, petitions, protests—all classic examples of “civic engagement” (Verba and Nie 1987). While recent scholarship on bureaucratic policymaking has shed light on sophisticated lobbying, especially by businesses, we know surprisingly little about the vast majority of public comments, which come from the lay public. The few studies to address the massive level of participation from the lay public (i.e., not professional policy influencers) tend to compare it (often unfavorably) to the participation of more sophisticated actors (Steven J. Balla et al. 2020) or suggest ways to improve the “quality” of citizen input. Raising the quality of citizen comments means making them more like the technical comments of lawyers and professional policy influencers (Cuéllar 2005; Cynthia R. Farina et al. 2011, 2012; Dmitry Epstein, Heidt, and Farina 2014; Cynthia R. Farina 2018; Mendelson 2011).

I argue that contrasting the quality of input from citizens and lobbying organizations is misguided. Indeed, “it can be difficult to distinguish an individual’s independent contribution from an interest-group-generated form letter” (Seifter 2016, 1313). Rather, to study public participation, we must attribute public engagement to the broader lobbying effort it supports. I show that most public comments in U.S. federal agency rulemaking are part of organized campaigns, more akin to petition signatures than “deliberative” participation or sophisticated lobbying. Moreover, nearly all comments are mobilized to support more sophisticated lobbying efforts. Comments from the lay public are neither “deliberative” nor “spam.” People participate because they are mobilized into broader lobbying efforts. Because nearly all mobilizing organizations are repeatedly lobbying, these public pressure campaigns are often broader than the policy they target. Often they aim to raise attention and build power for future policy fights.

Without an accurate and systematic understanding of public participation—group-mediated participation—in bureaucratic policymaking, it is impossible to answer normative questions about how participatory processes like public comment periods may enhance or undermine various democratic ideals. Surely, those who tend to engage are far from representative of the broader public (Verba and Nie 1987). That said, even a fairly elite segment of the public is likely more representative than the handful of political insiders who usually participate in bureaucratic policymaking. If the usual participants have “an upper-class accent” (E. Schattschneider 1942), does adding thousands of more voices dilute this bias? The answer depends on how people are mobilized. If the “usual suspects” mobilize public participation to create a misleading impression of broad public support for their policy positions, they may merely legitimize the demands of the same group of powerful interest groups that would dominate without broader public participation. If, however, public pressure campaigns are used by groups that are typically excluded or disadvantaged in the policy process, then public comment processes may democratize bureaucratic policymaking.

While practitioners and administrative law scholars have long pondered what to make of letter-writing campaigns targeting the bureaucracy, political scientists have had surprisingly little to say about this kind of civic participation and the role of public pressure in bureaucratic policymaking. Scholars trained in law tend to focus on the normative and legal import of public participation and pay less attention to how groups gain and wield power (notable exceptions include Coglianese 2001; Wagner 2010; Wagner, Barnes, and Peters 2011; Seifter 2016). Nearly all empirical studies of bureaucratic policymaking in political science journals exclude form letters from their analysis. While Coglianese (2001) and Shapiro (2008) suggested that mass comments may have important effects, including on the time it takes to make policy, studies addressing more than a few example cases have only appeared recently. The most comprehensive study to date (Moore 2017) finds less participation when agencies rely more heavily on expertise. Examining policies made by the Environmental Protection Agency, Potter (2017a) finds that advocacy groups mobilize more often than industry groups, and Steven J. Balla et al. (2020) find that form letters are cited less often and are less associated with policy change than comments written by lawyers and other professional policy influencers.

While this growing body of scholarship has improved our understanding of bureaucratic policymaking, public participation is still largely under-tilled empirical terrain on which to extend and evaluate theories about civic participation and pressure politics. Much of our knowledge about civic participation beyond voting comes from surveys and qualitative studies of particular groups. In contrast, models of bureaucratic policymaking focus on the participation of sophisticated lobbying groups. These models neither explain nor account for public pressure campaigns. Thus, civic engagement in general and organized public pressure in particular remain poorly understood in the context of bureaucratic policymaking.

Political scientists’ neglect of public pressure campaigns that target the bureaucracy is surprising given that some of the most contentious recent public controversies involve bureaucratic policymaking.3 Pressure campaigns are important because most people are only aware of bureaucratic policymaking when it is the target of a public pressure campaign. Indeed, because most agency policies receive so little attention, pressure campaigns often increase the level of public attention by several orders of magnitude. And as I show below, pressure campaigns have become more frequent. The ease of online mobilizing and commenting has, like other forms of participation (Boulianne 2018), greatly increased the number of policies on which thousands and even millions of people comment.

Figure 2.1: Regulations.gov Solicits Public Comments on Draft Agency Rules

The general failure to explain and account for public pressure campaigns in models of bureaucratic policymaking is also striking in light of how agencies advertise public comment periods as an opportunity for a voice in government decisions. The regulations.gov homepage solicits visitors to “Make a difference. Submit your comments and let your voice be heard” and “Participate today!” (Figure 2.1). A blue “Comment Now!” button accompanies a short description of each draft policy and pending agency action. Public comment periods on draft agency policies are described as “an important part of democracy” (WSJ 2017), “often held out as the purest example of participatory democracy in actual American governance” (Herz 2016, 1). Rossi (1997) finds that “courts, Congress, and scholars have elevated participation in rulemaking to a sacrosanct status…greater participation is generally viewed as contributing to democracy” (p. 2). And yet, political scientists have paid little empirical or theoretical attention to the role of public pressure in bureaucratic policymaking.

To fill this gap, I bring theories of conflict expansion and pressure tactics into theories of bureaucratic policymaking. Because theories of bureaucratic policymaking focus on the power of information and expertise in policymaking, I highlight how public pressure campaigns create new information about the political context (“political information”). Doing so reveals competing intuitions about the drivers of public participation, which I assess using a large new dataset of participation in federal agency rulemaking.

To begin to make sense of public participation in bureaucratic policymaking, I develop a typology of different kinds of participation, with implications for the normative value of participatory institutions. Because political participation is almost always a collective affair, this includes a typology of public pressure campaigns.

First, I develop and assess two theories of who should mobilize public pressure campaigns and why. Each theory has observable implications for which types of groups will run campaigns in different contexts. One stems from scholarship on bureaucratic decision-making and interest group lobbying. It predicts that groups with more resources will dominate all forms of lobbying, including public pressure campaigns. The other emerges from theories of democratic politics. It predicts that groups with fewer material resources but more popular support will more often use public pressure campaigns. To the extent that public pressure campaigns drive participation, the normative value of participatory processes like public comment periods depends on who organizes these campaigns.

Suppose public pressure campaigns follow the usual patterns of interest group lobbying, where the groups with the most resources dominate. In that case, the procedural legitimacy they provide is merely a veneer masking the influence of powerful political insiders. Instead of diversifying the available information, they would merely reinforce powerful insiders’ claims and issue frames. We would expect pressure campaigns to push policy further in the direction desired by the most powerful insiders.

Instead, if the usual suspects do not dominate public pressure campaigns, participatory processes may yet improve the democratic credentials of American policymaking, expand political oversight, and diversify the information available to policymakers. To the extent that public pressure tactics empower groups that are usually left out of the policy process, pressure campaigns may blunt the influence of powerful insiders. Thus, to understand the empirical effects or normative value of participatory processes like public comment periods, we first need to know who participates and why. To the extent that public participation is mobilized by campaigns, we need to know who is behind them.

Second, I offer a theory about the conditions under which we should see private and public interest group campaigns. I argue that public interest groups more often have incentives to launch public pressure campaigns than private interests. Private interests have incentives to sponsor campaigns (including astroturf campaigns) under much more limited conditions. Campaigns from private interests should thus be less common than campaigns from public interest groups. However, I argue, the resources required to run a campaign will lead a few large public interest groups to dominate.

To assess these theories, I assemble a new dataset of thousands of public pressure campaigns that collectively mobilized millions of public comments across three administrations from 2005 to 2020. Using a mix of qualitative hand-coding and computational text analysis, I identify the coalitions of groups behind each campaign and the type of interest group they represent.

I find that mass participation in bureaucratic policymaking is better explained by theories of democratic institutions and conflict expansion rather than existing theories of bureaucratic policymaking. In other words, participation is overwhelmingly organized by relatively broad public interest groups who aim to shift rather than reinforce the typical balance of power in the policy process.

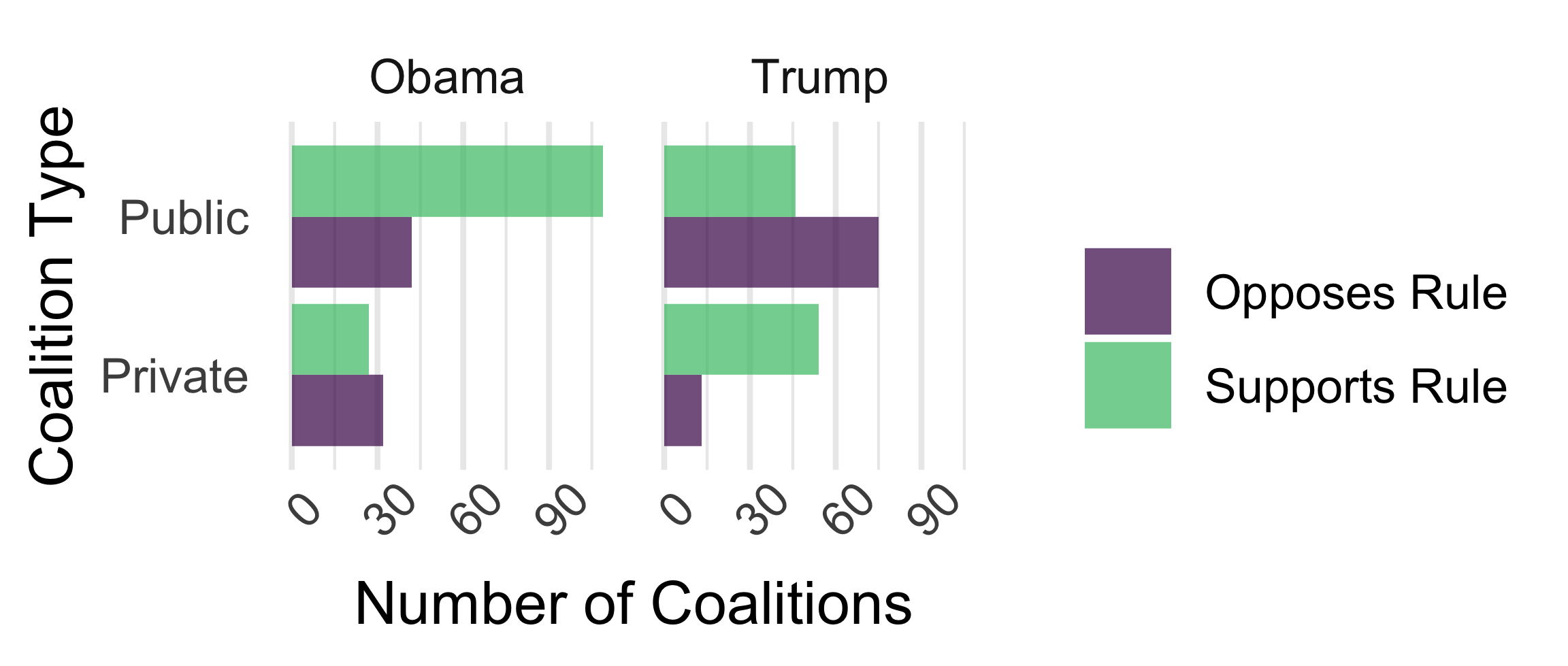

While greater public participation means that broader interests are represented, the resources and capacity required to mobilize people constrains which type of organization can use these tactics. Participation is overwhelmingly driven by the policy advocacy efforts of a few public interest groups. Indeed, just 100 advocacy organizations mobilized over 80 percent of all public comments. Traditional membership organizations and unaffiliated individuals account for a smaller portion, and “astroturf” campaigns are rare, almost exclusively arising in opposition to a large public interest group campaign, as my theory anticipates. One consequence of the concentration of organizing capacity is that public engagement in rulemaking is highly clustered on a few rules made salient by public pressure campaigns. Moreover, because these large national advocacy groups are overwhelmingly more aligned with the Democratic party, the politics of public participation in bureaucratic policymaking look very different under Democratic and Republican presidents. Public pressure is much more likely to support policies made by Democrats than Republicans.

I proceed in the following steps. Section 2.2 reviews the literature on civic engagement, democratic politics, and bureaucratic politics and then develops hypotheses about the causes of public engagement in bureaucratic policymaking. Section 2.3.1 introduces a novel dataset that systematically captures public participation in federal agency rulemaking. Section 2.3.2 outlines methods to assess my hypotheses using text analysis to leverage public comments as both content-rich texts and large-n observational data. Section 2.4 presents the results of this analysis.

2.2 Theory: Interest Groups as Mobilizers and Influencers

Interest groups play a critical role in American politics. As J. S. Hacker et al. (2021) observe,

[The United States’] institutional terrain advantages political actors with the capacity to work across multiple venues, over extended periods, and in a political environment where coordinated government action is difficult, and strategies of evasion and exit from regulatory constraints are often successful. These capacities are characteristic of organized groups, not individual voters. (J. S. Hacker et al. 2021, pg. 3)

Organized groups play at least two key functions in a large democracy: (1) organizing and mobilizing people around ideas and interests and (2) sophisticated lobbying to affect policy (Truman 1951). The next two subsections address each in turn.

2.2.1 The Mobilization of Interest

Mobilizing citizens and generating new political information (information about the distribution and intensity of policy preferences and demands) are key functions of interest groups in a democracy. Advocacy groups are “intermediaries between public constituencies and government institutions,” which often represent segments of the public with “shared ideologies or issue perspectives” (Grossmann 2012, 24). In doing so, public interest groups provide countervailing forces to business interest groups (J. J. Mansbridge 1992). Engaging citizens to participate in the policy process is a common strategy for groups to gain and exercise power (Mahoney 2007b), and thus a major driver of civic engagement (Skocpol 2003; Dür and De Bièvre 2007). Conflict among pressure groups, even those representing private interests, can lead to more majoritarian policy outcomes (S. W. Yackee 2009). Indeed, pluralist theories of democracy rely on interest groups to represent segments of the population in policymaking (R. Dahl 1958; R. A. Dahl 1961), though they may do so poorly (Elmer E. Schattschneider 1975; McFarland 2007; Seifter 2016).

2.2.1.1 Forms and Drivers of Civic Participation

Classic examples of civic engagement include participation in letter-writing, signing petitions, protesting, or attending hearings (Verba and Nie 1987). Importantly, Verba and Nie (1987) distinguish “citizen-initiated contacts” with the government from “cooperative activity” (p. 54). Political behavior research tends to focus on the choices of individuals. For example, survey research on political participation often studies activities like letter-writing as if they are citizen-initiated contacts rather than a group activity. Administrative law scholarship often discusses individual participants in rulemaking in a similar way. Cuéllar (2005) finds that members of the “lay public” raise important new concerns beyond those raised by interest groups. He advocates for reforms that would make it easier for individuals to participate and increase the sophistication of individual comments on proposed policies. However, most individual participation is not spontaneous and may be better classified as cooperative.

Cooperative activities are coordinated and mediated through organizations. By coordinating political action, public pressure campaigns expand civic participation in policymaking. I follow Verba and Nie (1987) in defining “civic participation” as “acts aimed at influencing governmental decisions” (p. 2). Some argue that participation only counts if it is deliberative, which mass comment campaigns are not (at least at the individual level). For example, Rossi (1997) argues mass comment campaigns are deleterious to civic republican ideals. Other criteria posed by normative theorists that participation should be “genuine,” “informed,” or “reasoned” are more difficult to assess. Normative theorists debate whether deliberation among a few people is preferable to a large number of people simply expressing their preferences. But empirically, public participation in bureaucratic policymaking is much more the latter (Shapiro 2008). In terms offered by J. Mansbridge (2003), public pressure campaigns are more about democratic aggregation than deliberation. D. Carpenter (2021) similarly characterized petitioning as “another model of aggregation” (p. 479) beyond elections.

Self-selection may not be ideal for representation, but opt-in forms of participation—including voting, attending hearings, or commenting on proposed policies—are often the only information decisionmakers have about public preferences. On any specific policy issue, most members of the public may only learn about the issue and take a position as a result of a public pressure campaign. Likewise, elected officials may only learn about the issue and take a position as a result of a public pressure campaign (Hutchings 2003). Campaigns inform agencies about the distribution and intensity of opinions that are often too nuanced to estimate a priori. Many questions that arise in rulemaking lack analogous public opinion polling questions, making mass commenting a unique source of political information. However limited and slanted, this information is directed at policymakers who may be unsure how the public and other political actors will react to their policy decisions.

Forms of civic participation beyond voting, such as protests and petitions, offer unique opportunities for minority interests in particular. Protests can be an effective mechanism for minority interests to communicate preferences to policymakers when electoral mechanisms fail to do so. Policymakers learn and take informational cues from political behaviors like protests (Gillion 2013). D. Carpenter (2021) finds similar potential for petitions to serve as a channel to raise “new claims” and influence policy beyond elections: “Petition democracy offers another model of aggregation, where numerical minorities could still make a case of quantitative relevance” (pg. 479). Numbers matter for protests and petitions, regardless of whether they represent a majority. These modes of preference aggregation often claim to represent a substantial segment of the public, perhaps a larger portion than those as passionately opposed to them.

2.2.1.2 Pluralism and Group Conflict in Democratic Theory

An organization can reshape the political environment by expanding the scope of conflict (Elmer E. Schattschneider 1975). Political actors bring new people into a political fight by using press releases, mass mailing, and phonebanking to drum up and channel public support. Conflict expansion strategies that attempt to engage the broader public are often called “going public” (Kollman 1998). Going public (also called outside lobbying or an outside strategy) contrasts with insider lobbying. Political actors go public when they expand the scope of conflict beyond the usual cadre of political actors. This strategy is used by presidents (Kernell 2007), members of Congress (Malecha and Reagan 2012), interest groups (Walker 1991; Dür and Mateo 2013), lawyers (Davis 2011), and even judges (Krewson 2019). For example, when presidents face difficult negotiations with Congress, they often use their bully pulpit to mobilize segments of the public to pressure elected representatives. Likewise, interest groups mobilize segments of the public to pressure policymakers as part of their lobbying strategy.4

Organizations that mobilize people to engage in policy debates (e.g., through letter-writing campaigns) go by many names, each with slightly different connotations. These include pressure groups (E. Schattschneider 1942), policy advocacy groups (Potter 2017a; Grossmann 2012), citizen groups (Jeffrey M. Berry 1999), and policy change organizations (McNutt and Boland 2007).

2.2.1.3 Public Pressure as a Resource

An organization’s ability to expand the scope of conflict by mobilizing a large number of people can be a valuable political resource (Lipsky 1968; Elmer E. Schattschneider 1975; Kollman 1998). In contrast to scholars who focus on the deliberative potential of public comment processes, I focus on public engagement as a tactic aimed at gaining power. Scholars who understand mobilization as a tactic (S. R. Furlong 1997; Kerwin and Furlong 2011) have focused on how organizations mobilize their membership. I expand on this understanding of mobilization as a lobbying tactic to include the broader audiences that policy advocacy organizations and pressure groups often mobilize. The broader audiences mobilized through public pressure campaigns are more akin to the concept of an attentive public (Key 1961) or issue public (Converse 1964).

S. R. Furlong (1997) and Kerwin and Furlong (2011) identify mobilization as a tactic. The organizations they surveyed reported that forming coalitions and mobilizing large numbers of people were among the most effective lobbying tactics. Studies of rulemaking stress the importance of issue networks (Gormley 1986; Golden 1998) and coalitions (J. W. Yackee and Yackee 2006; Nelson and Yackee 2012; M. A. Dwidar 2021; English 2019a). Other studies have described how organizations are behind form letter campaigns (Potter 2017a; Steven J. Balla et al. 2018; Steven J. Balla et al. 2020). Scholars have thus measured coalitions of organized groups and, separately, attached form letters to mobilizing organizations. I combine both of these approaches: defining mass mobilization as one tactic in coalition lobbying. I consider the lobbying coalition the unit of analysis and thus, unlike prior studies, attribute citizen comments to the coalition that mobilized them (not just the organization).

Second, Nelson and Yackee (2012) identify political information as a potentially influential result of lobbying by different business coalitions. While they focus on mobilizing experts, I argue that the dynamic they describe can be extended to public pressure campaigns:

Strategic recruitment, we theorize, mobilizes new actors to participate in the policymaking process, bringing with them novel technical and political information. In other words, when an expanded strategy is employed, leaders activate individuals and organizations to participate in the policymaking process who, without the coordinating efforts of the leaders, would otherwise not lobby. This activation is important because it implies that coalition lobbying can generate new information and new actors—beyond simply the ‘usual suspects’ —relevant to policy decisionmakers. (Nelson and Yackee 2012, 343)

Regarding political information, I extend this logic to non-experts. The number and distribution of ordinary supporters may matter because it suggests a public consensus, at least among some segments of the attentive public. (By “ordinary” people, I simply mean people who are not professional policy influencers.) Instead of bolstering scientific claims, a perceived public consensus bolsters political claims. To understand why groups organize public pressure campaigns, we must understand mass mobilization as a tactic aimed at producing political information.

2.2.1.4 Second-order Representation

The potential for “cheap talk” in claims of representation is a problem for the ability of groups to communicate credible political information. When lobbying during rulemaking, groups often make dubious claims to represent broad segments of the public (Seifter 2016). If agency staff do not trust an organizations’ representational claims, then engaging actual people may be one of the few credible signals of a broad base of support. This is especially true when organizations claim to represent people beyond their official members.

Advocacy organizations often claim to represent a large number of “members and supporters” (FWS-HQ-ES-2018-0007-47165). For example, in its comment on proposed regulations on internet gambling, the Poker Players Alliance claimed to represent “more than 840,000 poker enthusiast members” (TREAS-DO-2007-0015-0118). Many of these people became “members” when they signed up to play a free online poker game. However, the organization also claimed to have mobilized over 150,000 letters to members of Congress, which, if true, would indicate an active base of public support.

Membership organizations often claim to represent more than their membership. While political science theories often assume that membership organizations advocate for the exclusive private interests of their members, many membership organizations also lobby for broader policy agendas (Ahlquist and Levi 2013; J. J. Mansbridge 1992; Michener 2019). For example, healthcare worker unions frequently lead policy campaigns focused on public health and even issues like climate change. The link between an organizations’ policy agenda and the preferences of its members is sometimes more plausible than others.

Mobilizing people to write or sign public comments is one way—perhaps the best way—for organizations to provide evidence that they represent who they say they do. For example, the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), a top mobilizer of public comments, often claims to represent “3 million members and online activists” (NRDC 2021)—a figure that presumably includes anyone who has donated to or participated in one of its campaigns. Mobilizing comments is one way that NRDC can demonstrate active support for their specific position on a given issue.

To be sure, agency officials have a large amount of political information about their policy areas before soliciting comments. This information may vary across issues. For example, policymakers may better understand the number of people who support NRDC and their politics than they understand the supporters claimed by the Poker Players Alliance. Still, an organizations’ level of effort and the scale and intensity with which the attentive public responds to a pressure campaign may provide information about the politics of a given policy issue. A large showing for a campaign supporting a proposed policy may give bureaucrats a talking point with their political superiors or provide political cover to avoid congressional constraints. A surprising level of opposition may make agency leaders question their political tactics.5

Furthermore, if D.C. professionals primarily make advocacy group decisions (Skocpol 2003), these advocates themselves may be unsure of how broadly their claims resonate until potentially attentive segments of the public are engaged. A large amount of support may encourage professional policy influences to push officials harder to accommodate their requests.

Theorists debate whether signing a petition of support without having a role in crafting the appeal is a meaningful voice and whether petitions effectively channel public interests, but, at a minimum, engaging a large number of supporters may help broader interests distinguish themselves from truly narrower ones. It suggests that the organization is not entirely “memberless” (Skocpol 2003) in the sense that it can demonstrate some verifiable public support. An organization mobilizing its members and supporters to take some action lends weight to representational claims that might otherwise be indistinguishable from cheap talk claims that groups often make to represent broad constituencies. Demonstrated grassroots support is political information that may bolster a group’s representational claims.

The credibility of the signal that mass engagement provides may be complicated by “astroturf” campaigns, where organizations aim to project the image of a larger base of support than they truly have (McNutt and Boland 2007; Rashin 2017). To the extent that support can be effectively faked or inflated using astroturf tactics, the political information that pressure campaigns provide will be less accurate and thus less valuable to decisionmakers.

Astroturf campaigns that utilize faked evidence of mass support (e.g., fake petition signatures) bypass the public pressure and mass engagement step entirely, manifesting false political information. However, in a model where political information supports an organization’s broader lobbying efforts, providing fake political information is a risky strategy. Organizations lobbying in repeated interactions with agencies and an organization’s reputation—critical to its ability to provide credible technical information—may be harmed if policymakers learn that they provided false political information. One observable implication is that astroturf campaigns will often be anonymous or led by organizations that do not also engage in sophisticated lobbying. This may provide sophisticated lobbying organizations plausible deniability. However, because policymakers should rationally discount petitions submitted anonymously or by unknown organizations, fraudulent campaigns have little hope of influencing policy in this model. Compared to a model where political information is not mediated by groups that also engage in sophisticated lobbying, astroturf campaigns should be fairly rare if my theory is correct.

2.2.2 Lobbying in Bureaucratic Policymaking

Theories of interest-group influence in bureaucratic policymaking have focused more on sophisticated lobbying than the mobilizing functions of interest groups. Broadly, this scholarship has concluded that technical information is the currency of insider lobbying and that businesses are best positioned to influence bureaucratic policymaking. Empirical scholarship finds that economic elites and business groups dominate American politics in general (Jacobs and Skocpol 2005; Soss, Hacker, and Mettler 2007; Hertel-Fernandez 2019; J. Hacker 2003; Gilens and Page 2014) and rulemaking in particular. While some are optimistic that requirements for agencies to solicit and respond to public comments on proposed rules allow civil society to provide public oversight (Michaels 2015; Metzger 2010), most studies find that participants in rulemaking often represent elites and business interests (Seifter 2016; Crow, Albright, and Koebele 2015; Wagner, Barnes, and Peters 2011; W. F. West 2009; J. W. Yackee and Yackee 2006; S. W. Yackee 2006; Golden 1998; S. F. Haeder and Yackee 2015; Cook 2017; Libgober and Carpenter 2018).

Foundational scholarship on rulemaking (Scott. R. Furlong and Kerwin 2005; S. R. Furlong 1997, 1998; Kerwin and Furlong 2011) focuses on interest group lobbying. Theoretical models and empirical scholarship has focused on how interest groups help agencies learn about policy problems (S. W. Yackee 2012; Gordon and Rashin 2018; Daniel E. Walters 2019a). Formal models of rulemaking (Gailmard and Patty 2017; Libgober 2018) are information-based models where public comments reveal information to the agency. Legal and scientific information is so important that flooding policymakers with technical information is a highly effective lobbying strategy (Wagner 2010).

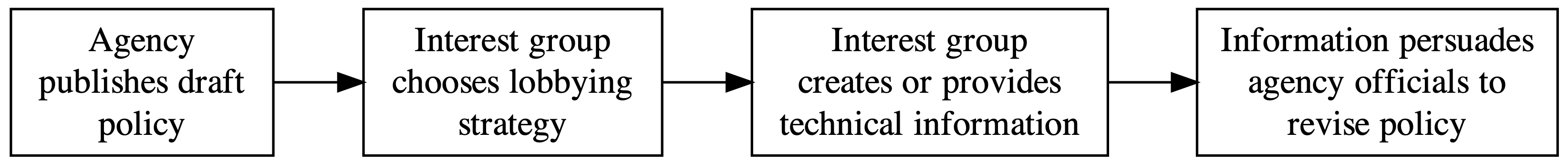

Figure 2.2 illustrates the “classic model” of insider lobbying that describes most rulemakings and nearly all scholarship on lobbying in bureaucratic policymaking to date. The first step in the policy process is the publication of a draft rule (Agency publishes draft policy). The first broadly observable step in the rulemaking process is usually an agency publishing a draft rule in the Federal Register.6 While organized groups certainly shape the content of draft policies (W. F. West 2004), the public portion of the policy process begins when the draft is officially published. Taking the publication of a draft policy as my starting point builds on the idea that “new policies create politics” (E. E. Schattschneider 1935).

After learning about the content of the policy, interest groups form concrete opinions about how exactly they would like the policy to change and develop a strategy to achieve their goals (Interest group chooses lobbying strategy) in the public comment stage of the policy process. These demands lead organizations to form lobbying coalitions and lobbying strategies that research may, in theory, observe. To date, most studies of rulemaking have focused on the power of expertise and novel technical information that may lead agency officials to re-evaluate their policy decisions (Information persuades agency officials to revise policy).

Figure 2.2: The ``Classic Model’’ of Interest Group Lobbying in Bureaucratic Policymaking

The contentious politics of mobilizing and countermobilizing that inspires most public engagement in policymaking have no place in leading models of bureaucratic policymaking and have largely been ignored by political scientists. To the extent that scholars of bureaucratic policymaking address the input of ordinary people and public pressure campaigns, both existing theory and empirical scholarship suggest skepticism that non-sophisticated actors merit scholarly attention.

2.2.2.1 What We Know About Mass Comment Campaigns

The concept of political information that I build upon comes from studies of lobbying coalitions and tactics (S. R. Furlong 1997; Nelson and Yackee 2012). However, this core scholarship on bureaucratic policymaking does not explicitly address mass comment campaigns. Indeed, nearly all scholarship on rulemaking excludes mass comments from both theory and data. Even studies that aim to assess the impact of the number of comments on each side exclude mass comments (e.g., McKay and Yackee 2007). To the extent that scholarship on the politics of rulemaking addresses the quantity rather than the quality of comments, most focus on the size of lobbying coalitions (i.e., the number of organizations) rather than the scale of public attention or pressure (J. W. Yackee and Yackee 2006; Nelson and Yackee 2012).

Most theoretical and empirical work addressing mass comment campaigns in rulemaking to date has come from administrative law scholars. Golden (1998) examines eleven rules randomly selected from three agencies, finding “a dearth of citizen commenters.” Cuéllar (2005) examines three different rules and found many comments from the “lay public” raising issues relevant to agency mandates. However, he finds that comments from the lay public were much less sophisticated than the comments of organizations and thus less likely to be cited by agencies. Mendelson (2011) finds that agencies often discard non-technical comments. While commenting and mobilizing others to comment has become easier, Coglianese (2006) finds that little else about the rulemaking process changed. Sunstein (2001) finds that the growth of the internet primarily facilitates more of the same kind of engagement among the “like-minded” (i.e., mass-commenting).

Political science scholarship on mass comment campaigns is limited to a few published articles (Shapiro 2008; Schlosberg, Zavestoski, and Shulman 2007; Steven J. Balla et al. 2018; Steven J. Balla et al. 2020), two unpublished dissertations (Moore 2017; Cook 2017)7, and an online report (Potter 2017a). Small adjacent literature in information technology and public administration journals document fraud in the public comment process (Rinfret et al. 2021) and gaps in training that bureaucrats receive (Rinfret and Cook 2019). Schlosberg, Zavestoski, and Shulman (2007) note that form letters differ from other comments. Shapiro (2008) investigates whether the number of public comments relates to the time between the publication of the draft and the final rule. With only nine observations, this study was unable to uncover general patterns but suggests that mass comments may be related to longer rulemaking processes. Moore (2017) finds that agencies that use high levels of expertise (as defined by Selin (2015)) receive fewer comments, possibly because mobilizing organizations perceive these rules to be less open to influence.

Cook (2017) examines three controversial Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) rules during the Obama administration. He found that high levels of public attention made it difficult for any one interest group to dominate. This finding suggests that the effects of lobbying may differ between rules with a lot of public attention and more typical rulemakings, where regulated business groups often dominate or lobby uncontested (J. W. Yackee and Yackee 2006). Representatives of both environmental and industry groups reported that mass comment campaigns were important. And the EPA noted that the majority of comments supported the proposed rule in all three cases.

One of the most theoretically developed and systematic studies to date is a short Brookings Institution report (Potter 2017a) that also focused on Obama-era EPA rules. Across 359 EPA rules, Potter (2017a) finds that 16 percent were subject to a mass comment campaign. She concludes that “advocacy groups and industry pursue different strategies with respect to comment campaigns.” In contrast to most forms of lobbying (which are dominated by industry groups), pressure campaigns are a tool mostly used by advocacy groups. Here, a “campaign” is form-letter comments associated with an organization (as identified by the EPA). On average, campaigns by advocacy organizations generated twice as many comments as industry-sponsored campaigns. Industry-sponsored campaigns were smaller and less likely to identify the sponsoring organization. Industry groups were much less likely to lobby unopposed than advocacy groups. That is, industry groups almost never sponsored campaigns on rules where environmental groups had not, but environmental groups sponsored campaigns even when industry groups did not. Potter (2017a) also finds that most mass comment campaigns supported EPA rules under Obama, with advocacy organizations in support and industry campaigns split between support and opposition.

In addition to extending Potter’s empirical work distinguishing the behavior of advocacy organizations and industry groups, I build on her theorizing about the possible reasons for sponsoring campaigns. Potter argues that public pressure campaigns can expand the scope of the conflict, help grow and maintain advocacy organizations, and give agency leaders political cover to pursue policies in the face of opposition. This chapter explicitly builds on these first two intuitions—how pressure campaigns expand the scope of conflict and grow advocacy organizations. Chapter 3 addresses the third—how public pressure campaigns may affect agency leaders’ political principals.

Steven J. Balla et al. (2018) also focuses on Obama-era EPA rules. They find campaigns occur across issue areas, including complex and economically significant actions. They find broad societal constituencies—such as environmentalists—to be more active in sponsoring campaigns than narrow interests. When industry-led campaigns occur, they divide along sectoral lines, with industries anticipating benefits arguing in favor of stringent regulations and industries forecast to bear the brunt of such actions sponsoring campaigns in opposition to the proposed rules.

Building on their previous work, Steven J. Balla et al. (2020) study 22 EPA rules and identify 1,049 “campaigns” on these rules—here, a campaign means a batch of form-letter comments associated with an organization, which Balla et al. code as “regulated” (e.g., a power plant) or a “regulatory beneficiary” (e.g., environmental groups). They find that the agency was more likely to reference the technical comments that groups submit than form letters. They also find that several types of observed policy changes (e.g., changes in the number of regulated entities and the date that the rule goes into effect) better align with changes requested by sophisticated interest group comments than those found in form letters. They conclude that “legal imperatives trump political considerations in conditioning agency responsiveness, given that mass comment campaigns—relative to other comments—generally contain little ‘relevant matter’” (Steven J. Balla et al. 2020, 1).

While Steven J. Balla et al. (2020) recognize the political nature of public pressure campaigns, they follow many of the administrative law scholars in comparing form letters to sophisticated technical comments. For example, their model compares the number of times the agency references the lengthy comments drafted by the Sierra Club’s Legal Team to the number of times the agency references the short form letters drafted by the Sierra Club’s Digital Team. In contrast, I argue that we should understand form letters as a tactic aimed at gaining power for coalitions and organizations that also submit sophisticated technical comments. Public pressure is not an alternative to sophisticated lobbying efforts; it is a resource for the broader task of persuading officials to change their policy decisions.

2.2.3 Incorporating Political Information

How, if at all, should scholars incorporate public pressure into models of bureaucratic policymaking? I argue that mass engagement produces potentially valuable political information about the coalition that mobilized it. To the extent that groups aim to influence policy, public pressure campaigns support sophisticated lobbying. Scholars should study public pressure as a potential complement, not an alternative to sophisticated lobbying. This means that the role that public pressure may play in policymaking depends on who mobilized it and why. The first step in understanding the potential impact of public pressure is to develop theories and testable hypotheses about the drivers of public participation.

In this section, I first develop two theories about the drivers of public participation in bureaucratic policymaking, one rooted in theories of group conflict and democratic politics and the other rooted in existing theories of interest-group lobbying in bureaucratic policymaking. I then offer a theory that specifies the conditions under which we should see different kinds of public pressure campaigns.

2.2.3.1 “Usual Suspects” or “Underdogs”

Existing scholarship points to two possible reasons why agencies may receive millions of public comments. From a conflict expansion perspective, groups that are disadvantaged by the status quo ought to utilize public pressure campaigns. Existing theories of lobbying the bureaucracy suggest that well-resourced and concentrated interests will dominate. Political information may thus play two distinct roles in policymaking with opposite effects depending on who mobilized it. The normative and empirical import of public pressure campaigns thus depends on who is behind them.

To the extent that well-resourced groups (the “usual suspects”) use public pressure campaigns to create a misleading impression of public support (often called “astroturf”), they serve to strengthen and legitimize demands of the same powerful interests that usually dominate bureaucratic policymaking. Here, just as groups with superior resources use them to flood policymakers with technical information (Wagner 2010), astroturf campaigns convert economic resources into political information—an impression of public support generated by signatures or form letters. Even groups with few members or a narrow or non-existent base of support among the public may create the appearance of public support by sponsoring an astroturf campaign. If the powerful business groups that dominate other forms of lobbying also dominate public pressure campaigns, these campaigns (and perhaps public comment periods themselves) are normatively suspect, providing a democratic veneer to economic power. Empirically, we would then expect public pressure campaigns to further advantage the most well-resourced interests.

The literature on conflict expansion suggests a different possible dynamic. To the extent that less-resourced groups (“underdogs”) use public pressure campaigns as a conflict expansion tactic, their role is the opposite: to push back against powerful interests that would otherwise dominate bureaucratic policymaking. The political information created by conflict expansion can reveal existing and potential support among attentive segments of the public. Through public pressure campaigns, groups that lack financial resources can convert latent public support into concrete political information that may cause policymakers to update their beliefs and change their decisions.

If public pressure campaigns are mainly a vehicle for public interest groups to convert a latent base of public support into influential political information supporting their representational claims or shining light on the policy process, then public comment periods may yet serve some of the informing, balancing, and democratic functions that practitioners and normative theorists desire. Empirically, we would then expect public pressure campaigns to disadvantage well-resourced interests that dominate most policy processes.

2.2.3.2 The Conditions Under Which Public and Private Interests Mobilize

This section draws on theories of interest group lobbying and conflict expansion to explain variation in mass engagement. First, I offer a framework for assessing the causes of mass engagement. Next, I argue that organizations may mobilize large numbers of people for several reasons with observable implications for observed patterns of public participation.

While most scholars have emphasized the lack of useful technical information in mass comments, a few have raised their role in creating political information. Cuéllar (2005) calls on agencies to pay more attention to ordinary peoples’ expressions of preference. Rauch (2016) suggests that agencies reform the public comment process to include opinion polls. Raso and Kraus (2020) suggest a similar reform whereby people could “upvote” comments with which they agree.

I build from a similar intuition that public pressure campaigns currently function like a poll or, more accurately, a petition, capturing the intensity of preferences among the attentive public—i.e., how many people are willing to take the time to engage. Indeed, many campaigns use the language of public opinion and petitioning. For example, a campaign by the World Wildlife Federation provided language explicitly claiming to have public opinion on its side. Its form letter cited an opinion poll, stating the following: “along with 80 percent of the American people, I strongly support ending commercial trade in elephant ivory in the U.S.” This suggests that public pressure campaigns aim to signal information about public opinion. A coalition led by another environmental group, Oceana, framed its mass mobilization effort to curb the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management’s 2017 Proposed Offshore Oil and Gas Leasing Program as a “petition signed by 67,275 self-proclaimed United States residents,” suggesting that organizations consider some mass-comment campaigns to effectively be petitions. In the same statement, Oceana also claimed the support of “more than 110 East Coast municipalities, 100 Members of Congress, 750 state and local elected officials, and 1,100 business interests, all of whom oppose offshore drilling,” suggesting that demonstrating support from members of the public and elected officials aim to provide similar kinds of political information.

Public pressure campaigns reveal the intensity of passions in attentive segments of the public. Because mass comment campaigns often presage or co-occur with other pressure tactics like protests and lobbying Congress, they may reveal information about other likely political developments.

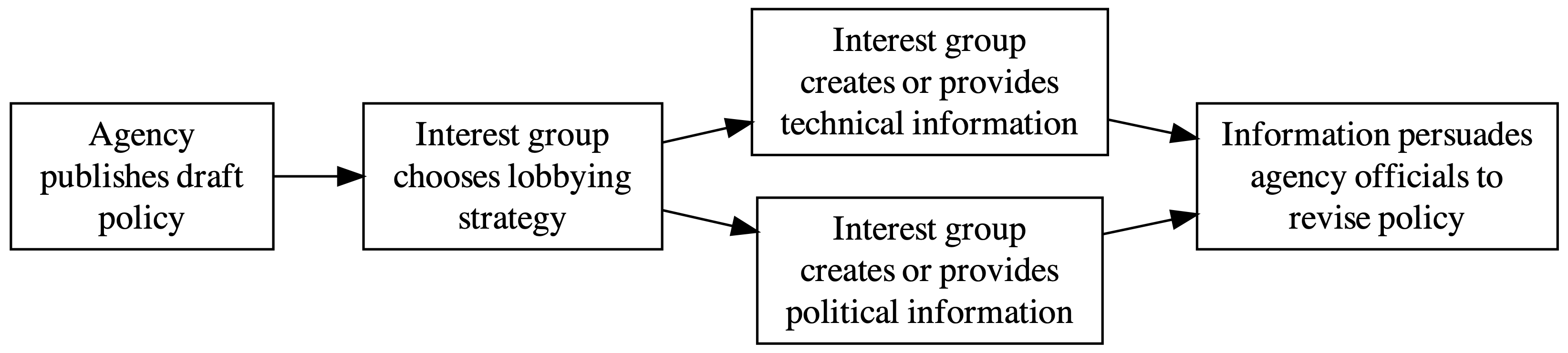

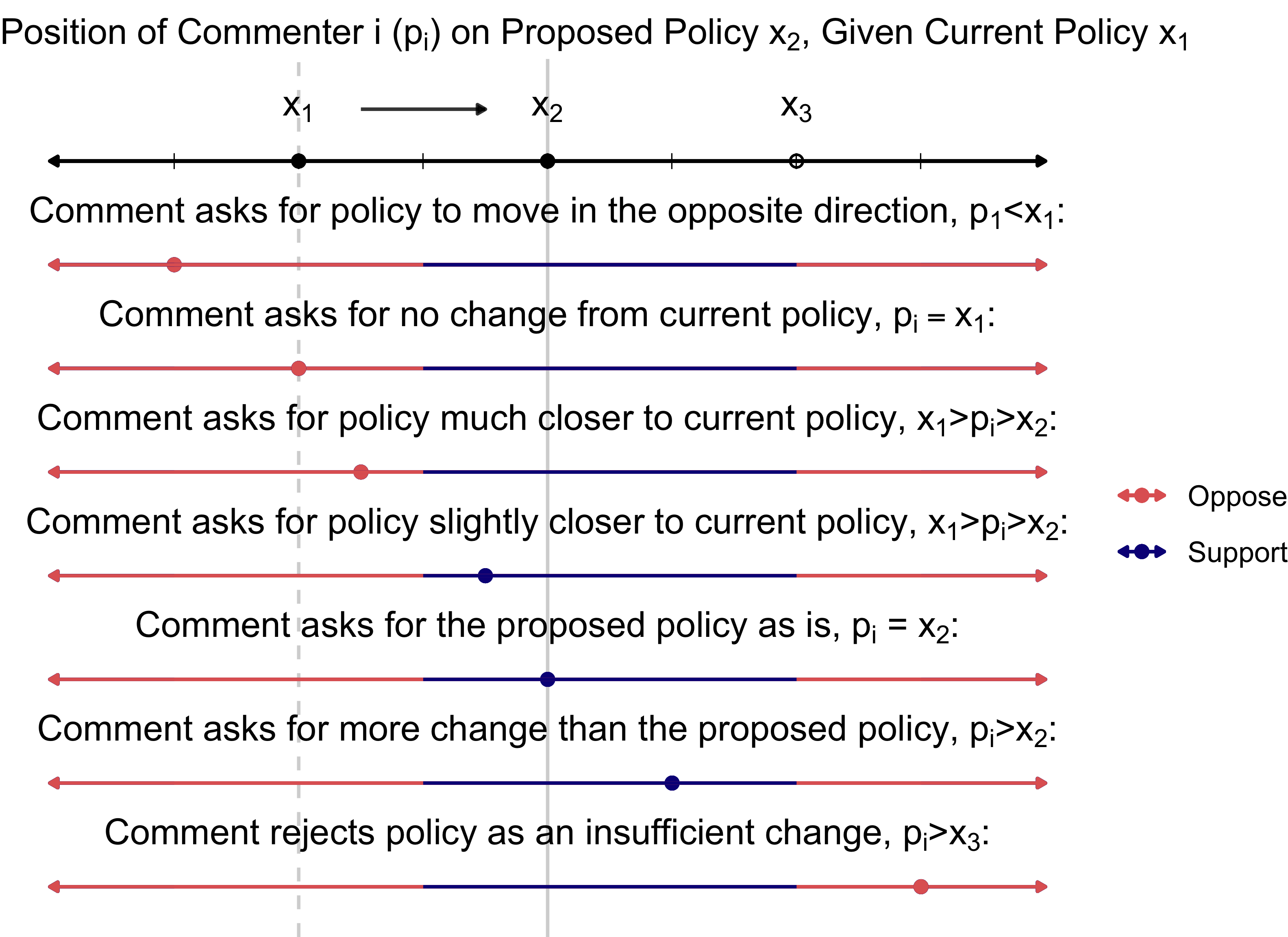

Building on theories of group conflict in democratic politics, I consider public demands to be a latent factor in my model of interest group lobbying during bureaucratic policymaking (Figure 2.3). Public demands shape the decisions of organizations as they choose a lobbying strategy. If they believe a large segment of the attentive public could be rallied to their cause, an organization may attempt to reveal this political information to policymakers by launching a public pressure campaign. That is, the extent to which latent public demands align with a group’s demands will affect its lobbying strategy, specifically whether it decides to launch a public pressure campaign.

Figure 2.3: Incorporating Political Information into Models of Interest Group Lobbying in Bureaucratic Policymaking

Figure 2.3 amends what I labeled the “classic model” of interest group lobbying from Figure 2.2 to incorporate political information. In the classic model, lobbying strategies are limited to inside lobbying strategies that aim to persuade officials with legal and technical analysis (Interest group creates or provides technical information). In the revised model presented in 2.3, interest groups may add a second strategy to support their legal and technical arguments with political information (Interest group creates or provides political information). For example, they may sponsor a public pressure campaign that generates political information about the attentive public. In this case, the organization provides technical information through sophisticated comments and organizes supporters to produce political information about their lobbying coalition through a mass comment campaign. This is a key feature of the theory: political information is mobilized to support a lobbying coalition’s sophisticated legal or technical lobbying effort, not as an alternative to sophisticated lobbying.

Interest groups with more latent public support should see a larger public response to a mobilization. The public response to the campaign (observed as the scale of public engagement in the policy process) depends on the extent to which the attentive public is passionate about the issue. A broader and more passionate attentive public will yield a larger volume of mass engagement than a narrower, less passionate base of public support. Thus the observed volume of mass engagement on a given side of a conflict can reveal political information about segments of the public. Broad engagement may produce several types of relevant political information. The most direct is the expressed “public opinion” that policymakers observe. I address other types of political information that mass engagement may create in Chapter 3.

The causal process visualized in Figure 2.3 may only operate under certain conditions. Policymaking institutions have different mechanisms for processing and incorporating technical and political information (the arrows between “Organization provides technical information” or “Organization provides political information” and “Agency officials revise policy”). Agencies may thus have different levels of receptivity to technical and political information.

Because lobbying organizations likely have some idea of the level of public support for their positions, one observable implication of this model is that lobbying organizations will be more likely to launch a public pressure campaign when they have more public support.

Instead of a public pressure campaign aimed at mobilizing supporters, an organization may attempt to bypass mass engagement by producing fake evidence of public support. However, as I describe below, this is a risky strategy.

2.2.4 Types of Pressure Campaign Motivations

The potential effects of public pressure campaigns depend, in part, on the aims of a campaign. Campaigns may pursue two distinct aims: (1) to advance policy goals or (2) to satisfy some audience other than policymakers (e.g., potential members or donors). Within each goal, campaigns can be further distinguished by whether their side is more likely to benefit or be harmed by an expansion of the conflict. Some groups have incentives to pursue policy goals by proactively launching a campaign, i.e., by “going public.” Others only have incentives to launch a campaign reactively after some other group has already expanded the scope of conflict. When groups aim to satisfy audiences other than policymakers and expect to win the policy conflict, campaigns are a form of credit claiming. Conversely, when a group anticipates losing the particular policy fight but still sees benefits in launching a campaign targeting non-policymaker audiences. I call this going down fighting. Proactively going public and reactively mobilizing after the other side has expanded the scope of conflict forms of outside lobbying. Credit claiming and going down fighting describe situations where an organization mobilizes for reasons other than influencing the policy at hand, like engaging or recruiting members.

Proactive campaigns. Coalitions “go public” when they believe that expanding the scope of conflict gives them an advantage. Because coalitions that “go public” should believe they have more intense public support, mass engagement is likely to skew heavily toward this side.

Going public is likely to be used by those who would be disadvantaged (those Elmer E. Schattschneider (1975) calls the ‘losers’) in a policy process with less public attention. More people may also be inspired indirectly (e.g., through news stories) or to engage with more effort (e.g., writing longer public comments) than people mobilized by the side with less public support. This is important because political information may be especially influential if decisionmakers perceive a consensus. The level of consensus among interest groups (Golden 1998; S. W. Yackee 2006), especially business unity (J. W. Yackee and Yackee 2006; S. F. Haeder and Yackee 2015), predicts policy change.8

Reactive campaigns. I theorize that when coalitions with less public support mobilize, it is a reaction to their opponents. Because the impression of consensus is potentially powerful, when one coalition goes public, an opposing coalition may countermobilize to emphasize that “both sides” have support from the broader public. Because these are coalitions with less intense public support, I expect such campaigns to engage fewer people. In the extreme, these campaigns may rely on various forms of deception (i.e., astroturf campaigns) to compensate for their disadvantage in genuine public support.

Credit claiming and going down fighting. Finally, campaigns may target audiences other than policymakers. When they expect to win, organizations may launch a “credit claiming” campaign to draw attention to and associate their organization with positive policy developments. When they expect to lose, organizations may “go down fighting” to fulfill supporters’ expectations. These more performative reasons for organizing a campaign may help engage existing supporters and recruit new members. For example, D. Carpenter (2021) finds that many anti-slavery petitions were this type of campaign, where “the most important readers of a petition are its signatories” rather than the policymakers to whom they are addressed.

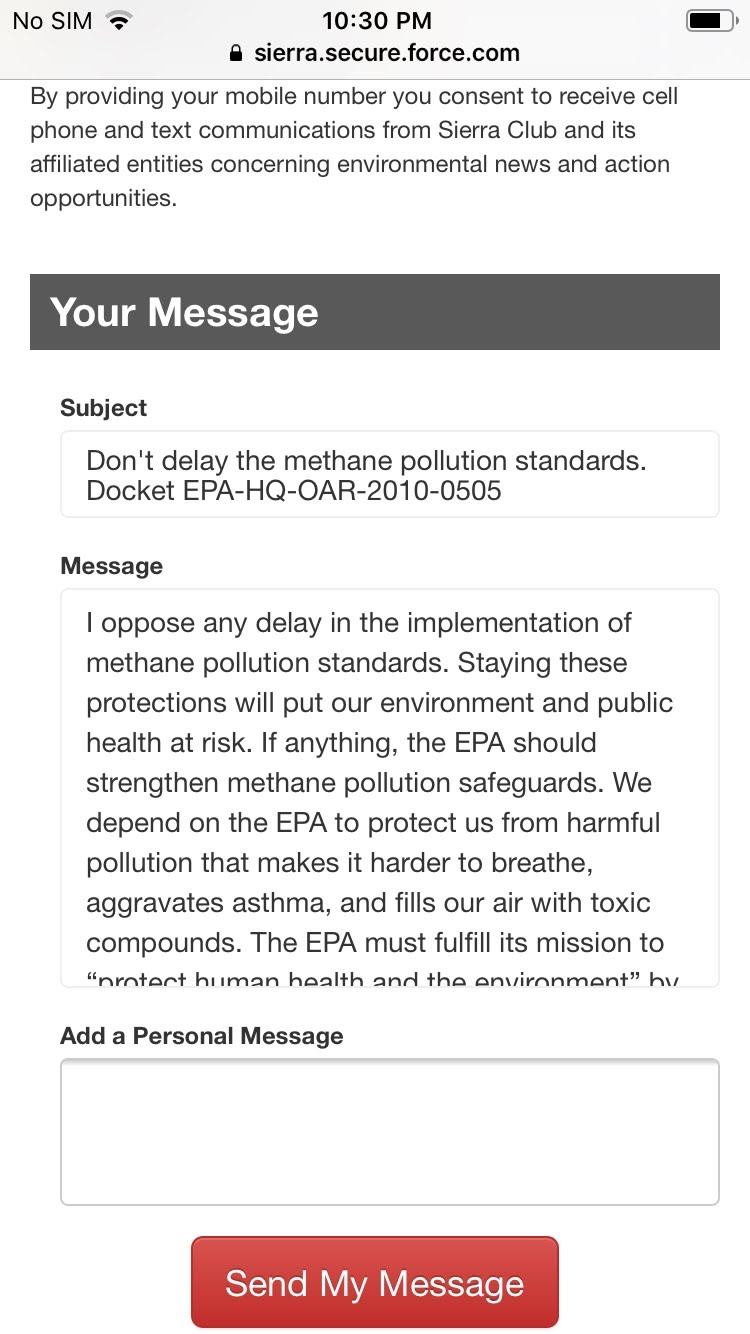

Figure 2.4: The Sierra Club Collects Contact Information Through Public Pressure Campaigns

Credit claiming and going down fighting campaigns may target member retention or recruitment, fundraising, or satisfying a board of directors. For example, as Figure 2.4 shows, the Sierra Club uses campaigns to collect contact information of supporters and potential members. Given the executive-branch transition between 2010, when the rule was initiated, and 2017 when it was delayed, the Sierra Club likely saw little hope of protecting methane pollution standards in 2017. Still, for members of the public who wanted to voice their opinion to the Trump administration, the Sierra Club created an easy way to do so, as long as users consented to “receive periodic communication from the Sierra Club.” While this campaign may have had little hope of influencing these particular policies, it may have increased awareness of air pollution and built contact lists that could help the Sierra Club fundraise and mobilize in future policy fights.

While “credit claiming” and “going down fighting” are unlikely to have immediate policy effects, they may affect future policies. Because interest groups and agencies both expect to “repeat endlessly” the policymaking process (Lindblom 1980), power built or demonstrated in one policy process may also be a political resource in future policy fights.

Through repeated interactions, organizations build power with respect to a constituency (Han 2014) and policymakers (Grossmann 2012). First, building contact lists or potential donors and supporters are a resource for future policy fights. Political support for a policy may depend on actors’ experiences with previous policies and their perceived relationship to the policy in question (Weir 1989). “Going down fighting” may be a particularly effective strategy in building awareness and power for future fights. In interviews with mobilizing organizations like the Sierra Club, Han (2014) finds that repeated engagement through a mix of online and in-person organizing can transform participants’ motivations and capacities for involvement. By building the capacities and motivations of their members and supporters, organizations increase their own capacity for future policy fights. For example, if one administration makes a policy that a large segment of the public can be mobilized to oppose, it may help organizations put the repeal of that policy on the agenda of the next administration.

Second, mobilizing in one policy fight helps organizations build a reputation among policymakers. A reputation for organizing public pressure campaigns may create an implicit credible threat that the organization may expand the scope of conflict. Organizations that mobilize members and create a long-lasting presence in Washington become, in the minds of policymakers and reporters, the taken-for-granted surrogates for these public groups (Grossmann 2012).

While more performative or power-building campaigns may engage many people, they are unlikely to inspire countermobilization. To the extent that public interest organizations mobilize for reasons other than influencing policy, opposing private interest groups with less public support have little reason to countermobilize. The reverse is not true. Private interest groups ought to only launch campaigns when the policy is in play. In these cases, public interest groups also have incentives to mobilize. Thus, member-funded public interest groups should be more common than campaigns sponsored by narrow private interests, simply because they have more occasions in which mobilizing has benefits. Campaigns sponsored by narrow private interests should occur in opposition to another campaign, but public interest groups have reasons to launch a campaign even when policy is unlikely to move.

Put differently, broader (often public) interest groups often have incentives to mobilize proactively when policy could be affected by expanding the scope of conflict. Where the policy is not in play, they may still benefit from credit claiming or going down fighting. Therefore public interest groups will often want to mobilize. In contrast, narrow (often private) interest groups do not benefit from expanding the scope of conflict and should thus only mobilize pressure campaigns reactively. Nor do they have audiences like members and donors that create performative reasons for mobilizing a pressure campaign.

In many cases, going public as a lobbying strategy is simultaneously an opportunity to engage and recruit members. Organizations often go public in order to influence policy and engage in power-building tactics at the same time. For example, the Sierra Club organized several “Thank you, EPA” campaigns, asking supporters to thank the Obama EPA for new draft environmental policies and urge the agency not to back down. These campaigns simultaneously (1) engaged members, (2) implied that the Sierra Club had advanced its policy agenda (implicit credit claiming), and (3) pressured policymakers to hold their course or strengthen policy rather than bend to industry pressures.

The extent to which a campaign genuinely aims to influence policy or is pursuing other logics may be difficult to distinguish in the observed public response. Indeed, multiple motivations may drive most campaigns, and members of the public may poorly understand the different chances of success in each case. However, lobbying organizations likely know their chances of success and should thus invest less in providing technical information when they see little opportunity to affect policy. By identifying cases where coalitions engage in large public campaigns without corresponding investment in technical information, we may be able to assess whether countermobilization is indeed less likely in these cases.

2.2.5 Hypotheses About the Drivers of Mass Mobilization

The observable implications of the theory described above suggest several testable hypotheses.

First, public comments will differ in several ways depending on whether most public participation is individuals acting alone or organized and mediated through organizations their pressure campaigns. The solicitation on regulations.gov—“Let your voice be heard”—suggests that individuals are expressing themselves directly. Indeed, anyone can write a letter or type a comment in the text box on regulations.gov, and many people do. Individuals acting on their own submit content ranging from obscenities and memes to detailed personal accounts of how a policy would affect them and even poetry aimed at changing officials’ hearts and minds. Comments submitted by individuals acting alone should not have a large share of text copied from elsewhere. They should not reference an organization or be mailed or uploaded in bulk by an organization.

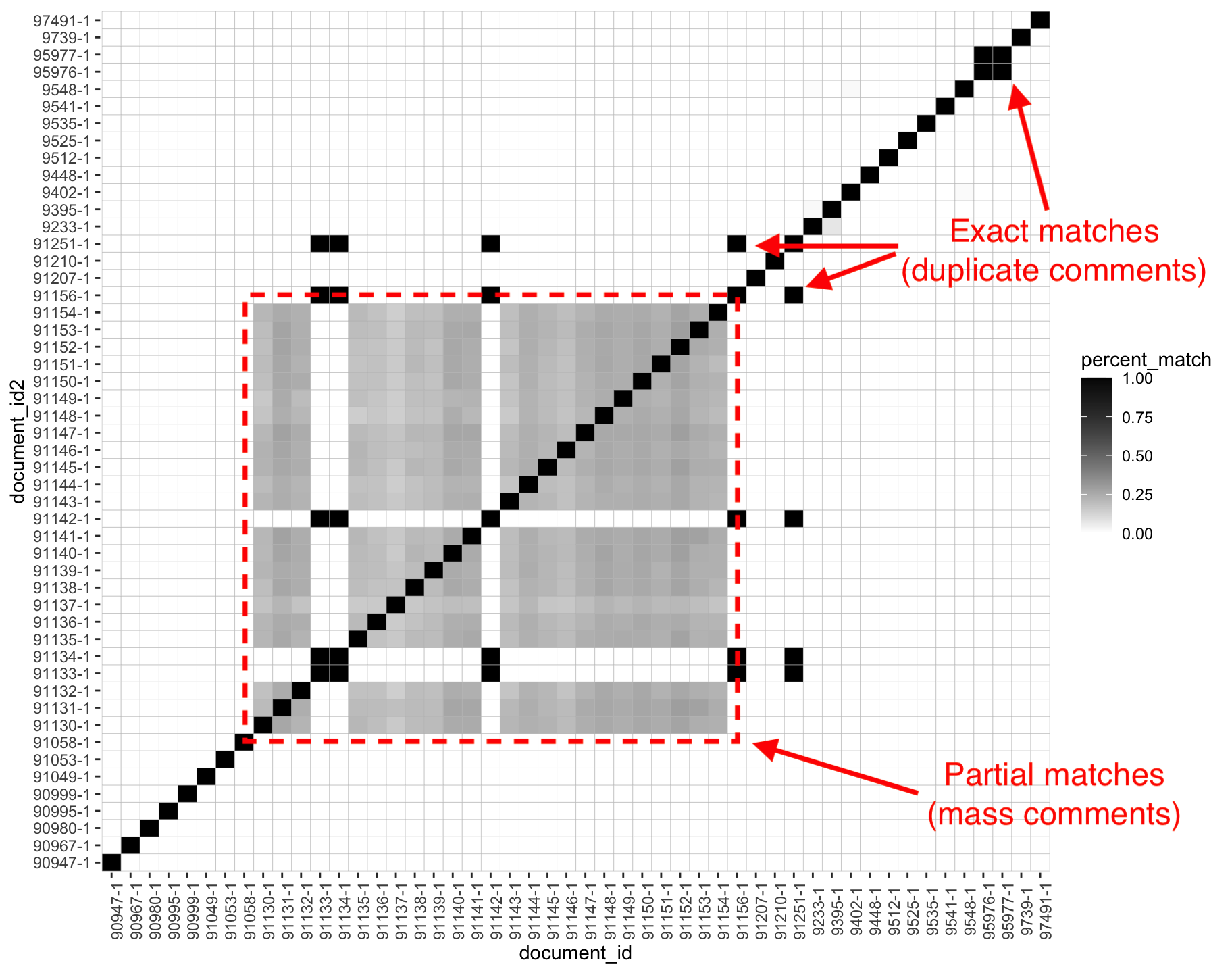

In contrast, to the extent that participation is mediated through public pressure campaigns, as my theory suggests, public commenting should show signs of “cooperative activity.” Comments from people who were mobilized as part of a campaign differ from those of individuals acting on their own in two observable ways: First, they often mention the name of the organization that mobilized them. Second, the text is often similar or identical to other comments in the campaign, reflecting coordination through form or template letters. These features eliminate the novel informational value that Cuéllar (2005) and others seek to locate in individual comments. If comments reference an organization that mobilized them, they likely have little more to offer than what the more sophisticated organization has already provided. If comments are identical, they certainly provide no new technical information.

While observers frequently talk about ordinary people engaging in policymaking as individuals, political science theory suggests that an organized group will almost always mediate the participation of individuals who are not professional policy influencers. Political science has shown that national politics in the United States is the terrain of organized groups. Given the technocratic nature of bureaucratic policymaking, “citizen-initiated contacts” should be especially rare.

From a behavioral perspective, Hypothesis 2.1 posits that individuals are more likely to engage in behaviors like letter-writing and petition-signing as part of coordinated and cooperative activity. The barriers to individual participation make “citizen-initiated contacts” on matters of national policy relatively rare. Organized campaigns overcome these barriers by informing, motivating, and reducing the costs of participation.

Second, I argue that public pressure tactics complement rather than substitute for sophisticated technical lobbying. Whereas previous studies compare mass comment campaigns to technical lobbying efforts, I argue that the relevant unit of analysis is the lobbying coalition. Coalitions may use both sophisticated technical lobbying and public pressure tactics.

From a behavioral perspective, Hypothesis 2.2 posits that decisionmakers in lobbying organizations do not confront a choice of whether to pursue an inside or outside strategy; it is a choice between an inside strategy (the norm) or both an inside and outside strategy because public pressure campaigns lend political support to more sophisticated legal and technical arguments for specific policy changes.

Testing Hypothesis 2.2 requires that we group organizations into lobbying coalitions. It predicts that coalitions that use public pressure campaigns also include groups that engage in sophisticated lobbying. To the extent that coalitions using outside strategies do not also use inside strategies would be evidence against Hypothesis 2.2.

Third, while lobbying coalitions may form around various material and ideological conflicts, public interest groups are more likely to be advantaged by going public, credit claiming, or going down fighting, because they are organizations primarily serving a broad idea of the public good rather than the narrow material interests of their members. Indeed, Potter (2017a) finds that advocacy group-driven campaigns mobilize far more people on average than industry-driven campaigns on EPA rules.

Building on T. Lowi (1969) and Wilson (1989), I theorize that mass mobilization is more likely to occur in conflicts of public versus private interests or public versus public interests (i.e., between coalitions led by groups with distinct cultural ideals or desired public goods), provided they have sufficient resources to run a campaign. If true, one implication is that mass mobilization will systematically run counter to concentrated business interests where they conflict with the values of public interest groups with sufficient resources to mobilize.

When policy conflicts pit broad public interests against narrower private interests, the public interest groups more often have incentives to launch public pressure campaigns, both for policy and organizational reasons. Because outside lobbying can alter the decision environment, those who have the advantage in the usual rulemaking process (where a more limited set of actors participate) have little incentive to expand the scope of the conflict. Additionally, I argue, public interest groups have greater incentives than businesses to launch public pressure campaigns for reasons other than influencing policy. Both policy and non-policy reasons to launch a campaign suggest that public interest groups will use outside strategies more often.

Hypothesis 2.3 may be evaluated in absolute terms–whether most public pressure campaigns are launched by public interest groups—or relative terms—whether public interest groups are more likely to use public pressure campaigns when they lobby than private interests are.

The inverse could also be true. Business groups that are already advantaged in the policy process may leverage their superior resources to further mobilize support or bolster claims that they represent more than their private interest. If mobilization most often takes this form, this would be evidence against Hypothesis 2.3 and Schattschneider’s argument that it is the disadvantaged who seek to expand the scope of the conflict.

Fifth, if the success of a mobilization effort is moderated by latent public support, as my theory asserts, broader public interest group coalitions ought to mobilize more people for a given level of mobilization effort (e.g., spending or solicitations). That is, the scale and the intensity of public engagement depend on preexisting support for the proposition that people are being asked to support, and public interest groups more often have broad public support than narrow private interests.

From a behavioral perspective, Hypothesis 2.4 suggests that the average person is more easily mobilized to sign a form letter from a public interest group than a private interest group.

Notwithstanding the incentive structure that should lead coalitions advancing broad public interests to mobilize public support more often and more successfully than narrow private interests, resources and capacity are still necessary conditions to run a campaign. Most organizations that are disadvantaged in the policy process also lack resources to launch mass mobilization campaigns. This means that public pressure tactics are only an option for a small subset of large public interest organizations.

Mobilizing people for a particular policy fight requires a significant organizing capacity. McNutt and Boland (2007) calls these formations “policy change organizations.” In contrast to membership organizations, they exist more to organize public pressure toward a set of policy goals than to serve a defined membership.

If instead, lay commenters are mobilized through their membership organizations, as Kerwin and Furlong (2011) suggest, a large campaign of, say, one million people would generally require a large collection of membership organizations. Very few organizations have a million members. Those that do are unlikely to mobilize all of them, so mobilizing many people through membership organizations would likely require a large coalition of membership organizations. We would expect commenters to identify themselves as members of these many organizations.

Finally, if the theory of conflict expansion posited by Elmer E. Schattschneider (1975) is correct, narrow private interests only have incentives to mobilize public support to counteract an opposing campaign. If private interest groups like businesses primarily use public pressure campaigns reactively to counter a message of public consensus advanced by an opposing lobbying coalition, we should rarely see private interest groups lobbying unopposed.

Hypothesis 2.6 would be supported by evidence that public interest group coalitions more often lobby unopposed than private interest groups.

The next section outlines the data and methods I use to evaluate these hypotheses.

2.3 Testing the Theory

To assess my theory about which groups should mobilize public participation in bureaucratic policymaking, I use public comments in federal agency rulemaking. However, my theories and methods should also apply to other kinds of political engagement, such as through social media or protests and other political decisions, including state-level rulemaking.

2.3.1 Data

I collected a corpus of over 80 million public comments via the regulations.gov API. 58 million of these comments are on rulemaking dockets. I then linked these comments to other data on the rules from the Unified Agenda and Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs Reports. Summary statistics for these data are available in the Appendix.

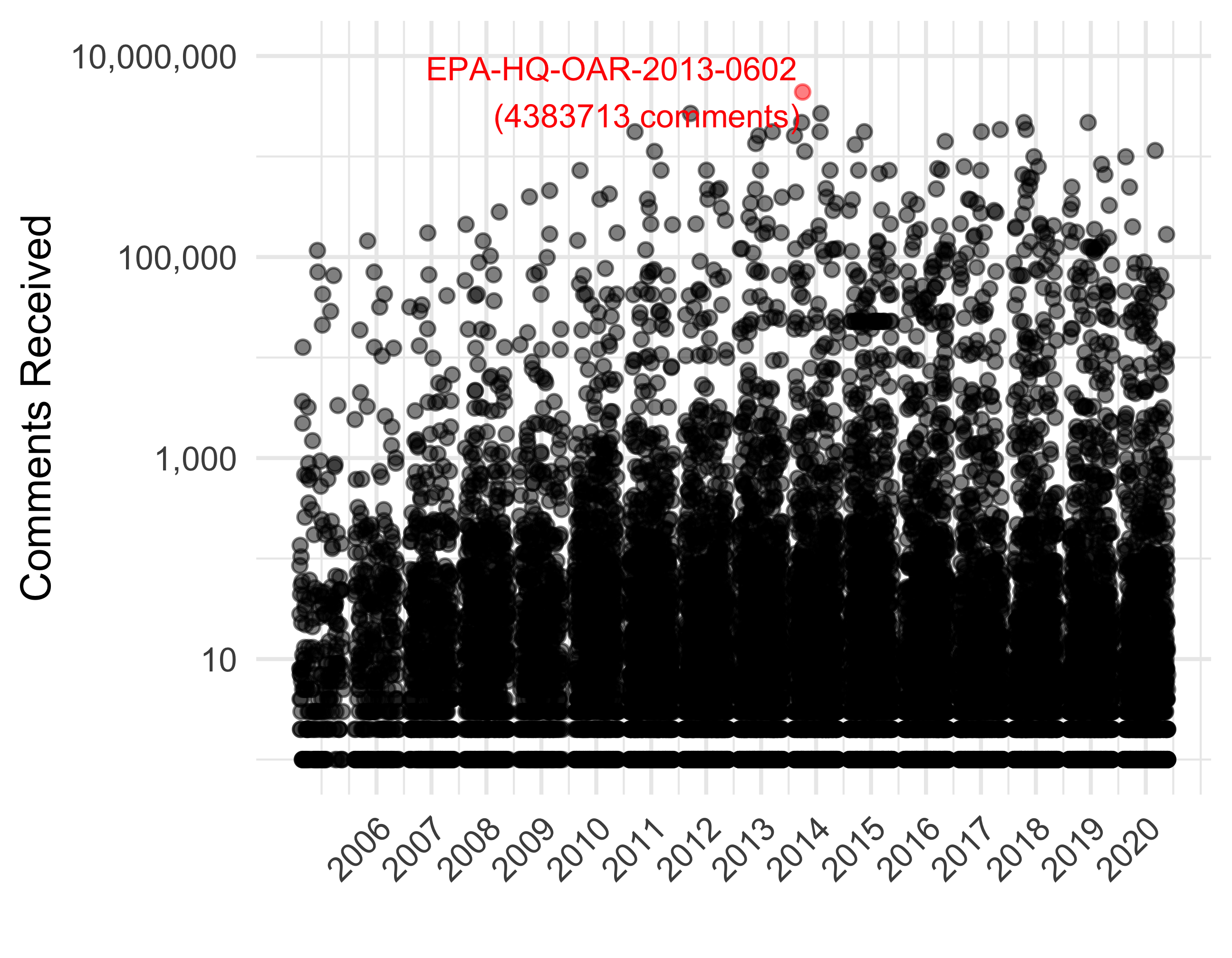

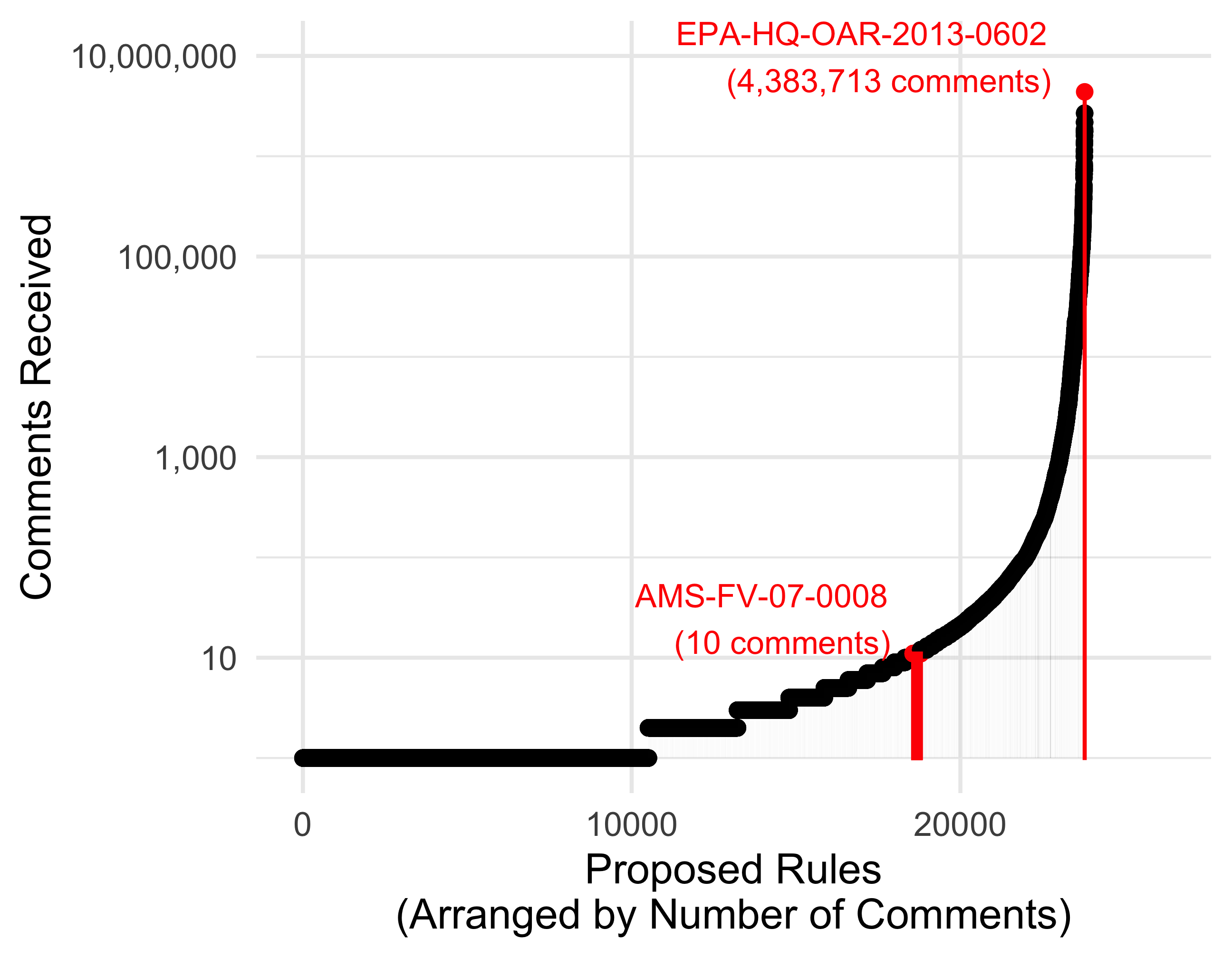

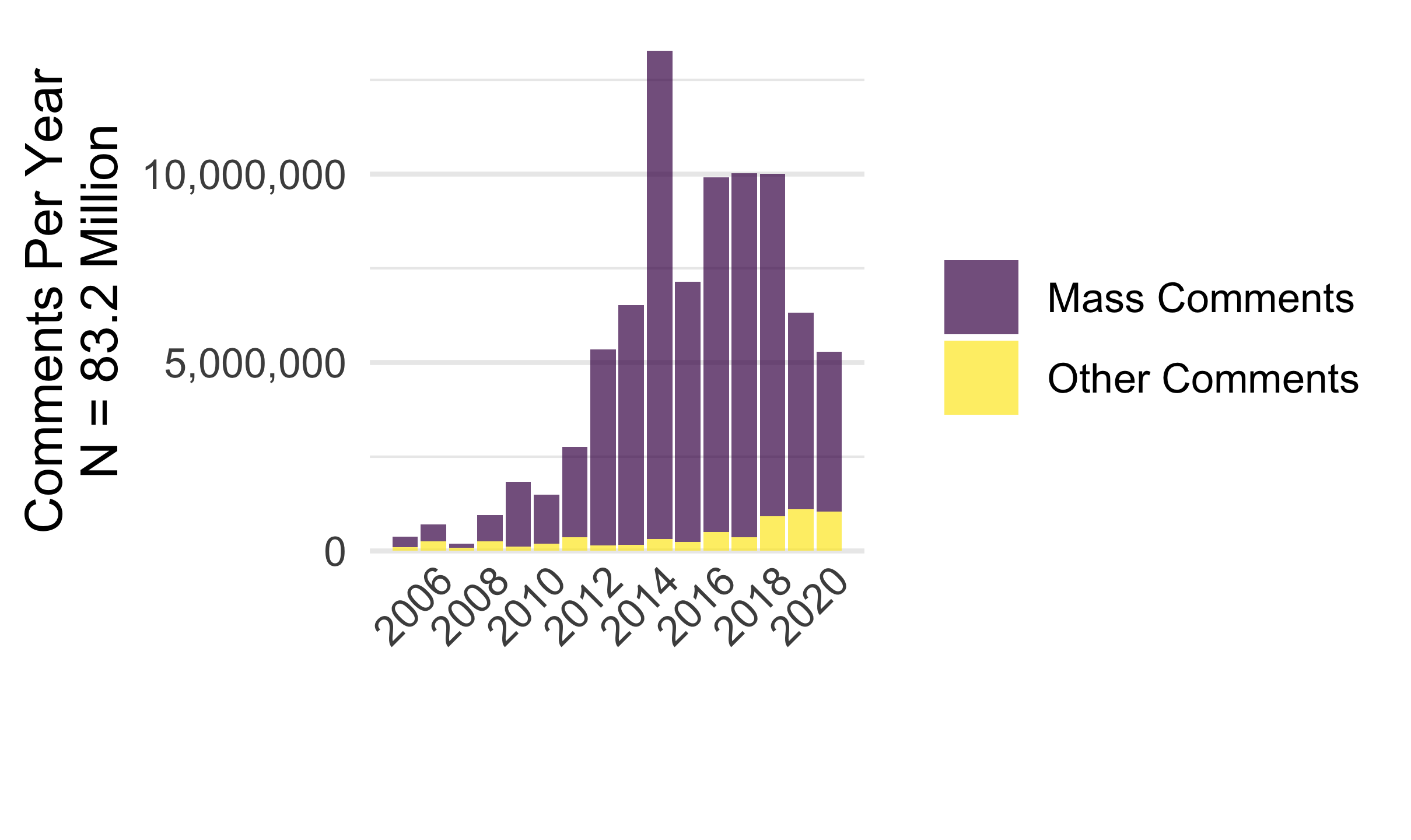

From 2005 to 2020, agencies posted 44,774 rulemaking dockets to regulations.gov and solicited public comments on 42,426. Only 816 of these rulemaking dockets were targeted by one or more public pressure campaigns, but this small share of rules garnered 99.07 percent (57,837,674) of all comments. Nearly all of these comments are form letters. The top 10 rulemaking dockets account for 33.74 percent (19,695,536), of all comments in agency rulemaking. Again, nearly all of these are form letters.

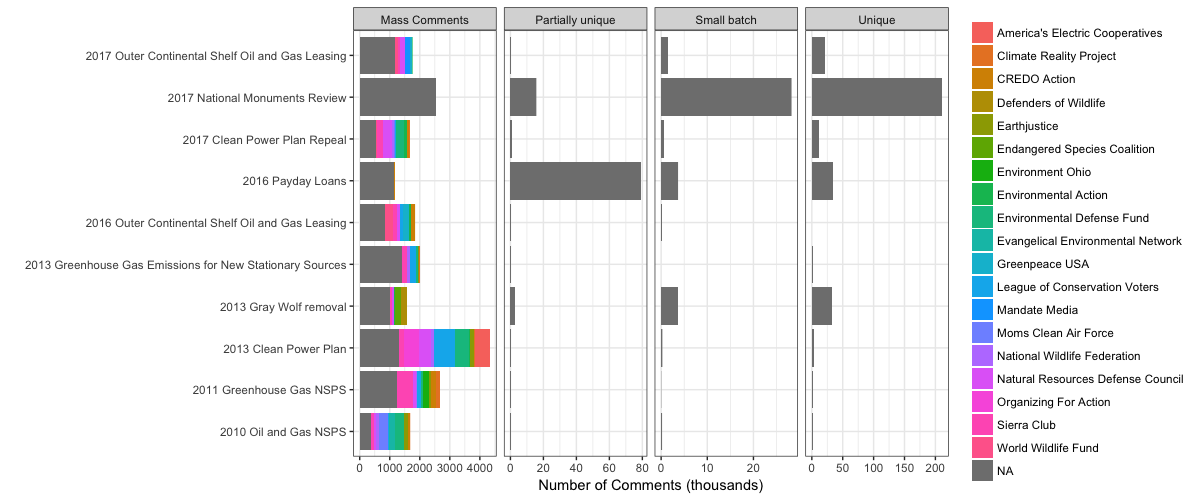

Table 2.1 shows the rules that received the most comments on regulations.gov. Proposed rules that have attracted the most public attention have been published by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the Department of Interior (DOI), the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM), the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), and Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS). The most commented-on rule was the 2013 “Clean Power Plan”—the Obama administration’s flagship climate policy.

| Docket ID | Docket Title | Total Comments |

|---|---|---|

| EPA-HQ-OAR-2013-0602 | Standards of Performance for Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Existing Sources: Electric Utility Generating Units | 4,383,713 |

| EPA-HQ-OAR-2011-0660 | Greenhouse Gas New Source Performance Standard for Electric Generating Units | 2,683,228 |

| EPA-HQ-OAR-2013-0495 | Review of Standards of Performance for Greenhouse Gas Emissions from New, Modified, and Reconstructed Stationary Sources: Electric Utility Generating … | 2,178,478 |

| EPA-HQ-OAR-2017-0355 | Repeal of Carbon Dioxide Emission Guidelines for Existing Stationary Sources: Electric Utility Generating Units; Emission Guidelines for Greenhouse Ga… | 1,853,582 |

| EPA-HQ-OAR-2010-0505 | Oil and Natural Gas Sector – New Source Performance Standards, National Emission Standards for Hazardous Air Pollutants, and Control Techniques Guide… | 1,761,990 |

| FWS-HQ-ES-2013-0073 | Removing the Gray Wolf from the List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Maintaining Protections for the Mexican Wolf by Listing It as Endangere… | 1,611,111 |

| CFPB-2016-0025 | Payday, Vehicle, Title and Certain High-Cost Installment Loans | 1,413,787 |

| BLM-2013-0002 | Oil and Gas; Hydraulic Fracturing on Federal and Indian Lands | 1,348,563 |

| FWS-HQ-IA-2013-0091 | Revision of the Special Rule for the African Elephant | 1,315,513 |

| CEQ-2019-0003 | Update to the Regulations Implementing the Procedural Provisions of the National Environmental Policy Act | 1,145,571 |

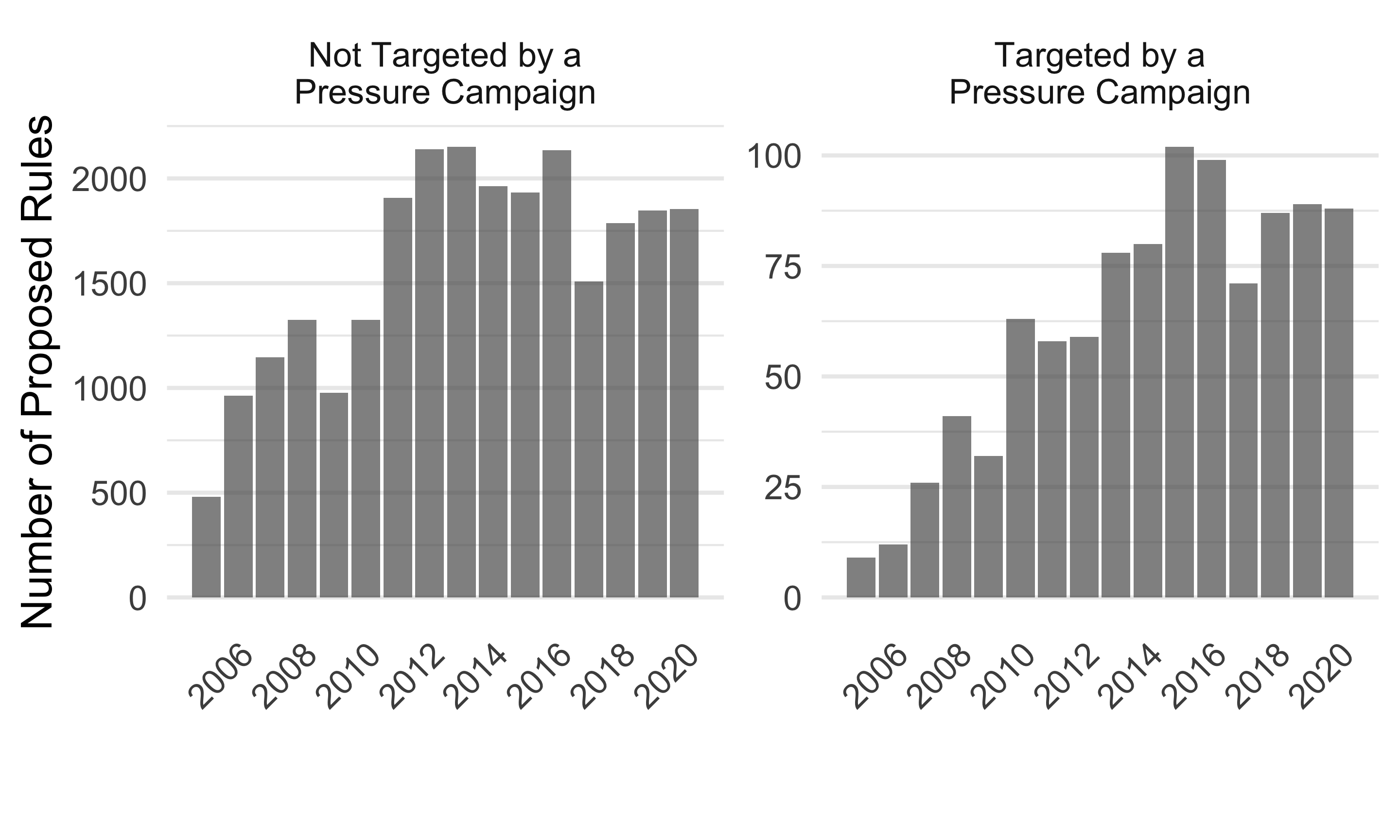

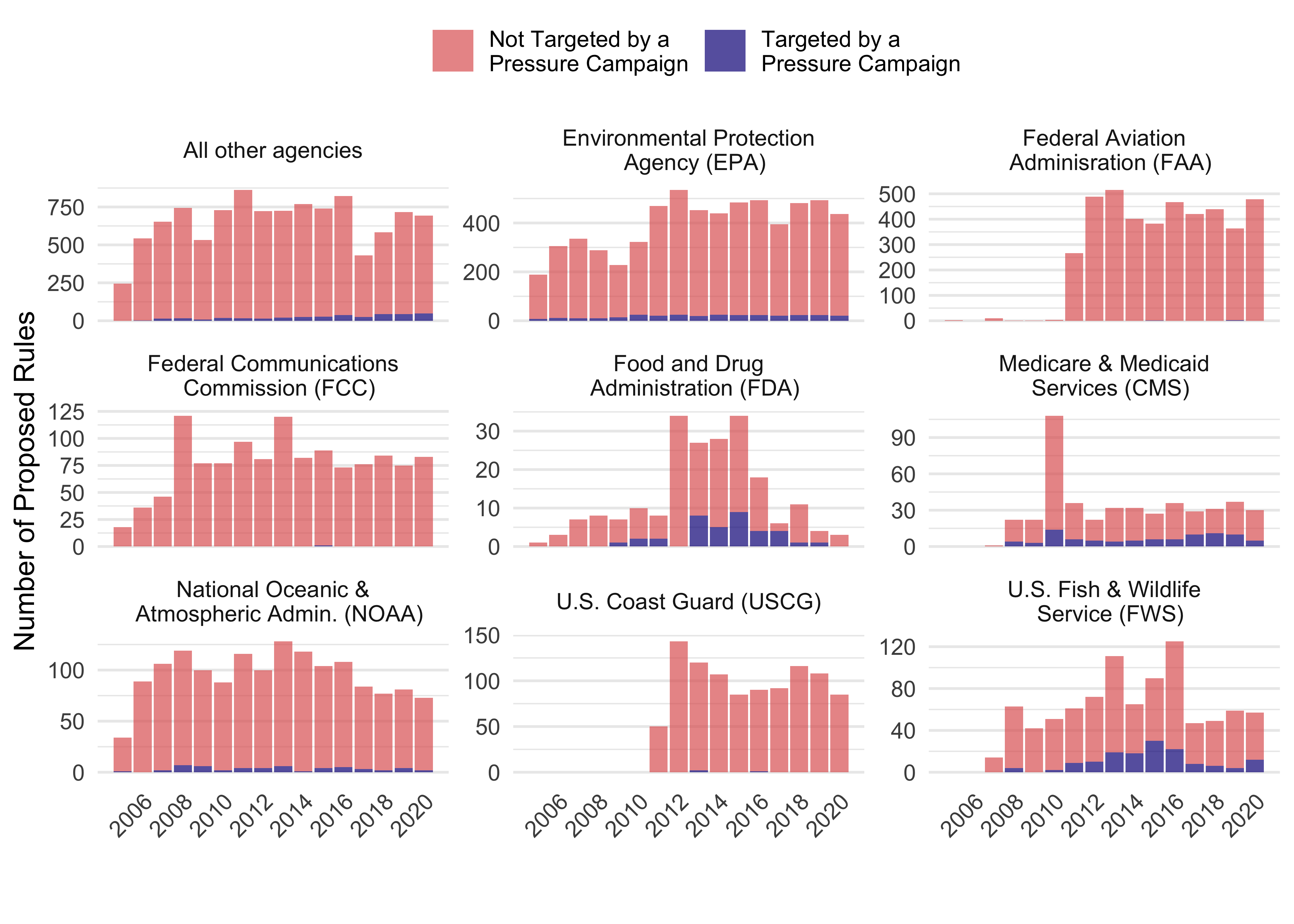

Figure 2.5 shows a massive rise in the number of proposed rules targeted by public pressure campaigns (the bottom panel), greater than the overall increase in the number of proposed rules posted for comment on regulations.gov (the top panel). To some extent, the increase from 2005 to 2010 results from agencies using regulations.gov more systematically in the years after its launch in 2003. But the ease of online organizing has also increased the frequency of public pressure campaigns. As mentioned earlier, less than 5 percent of proposed rules each year are targeted by a pressure campaign (note the necessary difference in the y-axes). However, this share is growing.