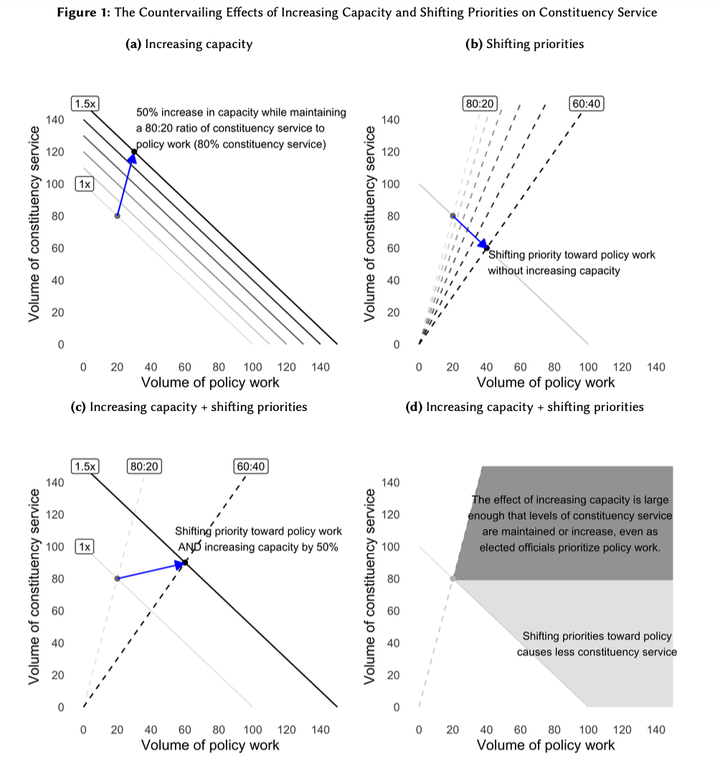

When elected officials gain power, do they use it to provide more constituent service or affect policy? The answer informs debates over how legislator capacity, term limits, and institutional positions affect legislator behavior. We distinguish two countervailing effects of increased institutional power: shifting priorities and increased capacity. To assess how institutional power shapes behavior, we assemble a massive new database of 611,239 legislator requests to a near census of federal departments, agencies, and sub-agencies between 2007 and 2020. We find that legislators prioritize policy work as they gain institutional power (e.g., become a committee chair) but simultaneously maintain their levels of constituency service. Moreover, when a new legislator replaces an experienced legislator, the district receives less constituency service and less policy work. Rather than long-serving and powerful elected officials diverting attention from constituents, their increased capacity enables them to maintain levels of constituency service, even as they prioritize policy work.

The Effects of Shifting Priorities and Capacity on Policy Work and Constituency Service

Evidence from a Census of Legislator Requests to U.S. Federal Agencies